Greetings, with two very different takes on what a vibrant inner life might look like.

(And why it may matter.)

It’s a lingering depth/soul-psychology theme that’s surfaced of late with diverse news events and public people, from hit-biopic physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer to newly eulogized singer Jimmy Buffett.

First on a logistical note, today’s edition was gathered quickly and completed early for the best of reasons: Grand Miz E and family here with an impromptu weekend visit to seize some remaining sunlit days with warm lake waters. So this is still largely a collection of selected quote-excerpts from two articles discovered this week. More thought and comment on their many elements will show up in future editions.

Title themes

After the corny wordplay with interior design, “that is NOT all-there-is” replies to the question posed in a 60’s-era pop song recorded by Peggy Lee. Perhaps the most utterly futile and depressing song ever, its repeatedly intoned refrain went:

“Is that all there is? Is that all there is? If that’s all there is, my friend, then let’s keep dancing…”

The song itself was a bit before my memory recall of such things in the adult world. But it must have powerfully expressed the zeitgeist, for it shows up in a lot of period-movies and programs like AMC’s Mad Men. As that show’s Betty Draper character experienced, this was the post-WWII peak of Freudian psychoanalysis on the mind-scape of American men and women.

Maybe that’s why the song brings to mind Freud’s often-quoted end-goal of his pioneering work. He believed that with enough psychoanalysis our unconscious inner life can be emptied of all of what he saw as its archaic, infantile, difficult, weird and otherwise undesirable contents and habits unfortunately planted in our childhoods. Through analysis, Freud assured, this emptying would ever-after replace our neurotic misery… with ordinary unhappiness.

(Great, where do we sign up?!!)

That seems a little like opening Pandora’s Box — on purpose and without even the solace of Hope remaining inside.

That essential Hope is a common thread in today’s two examples.

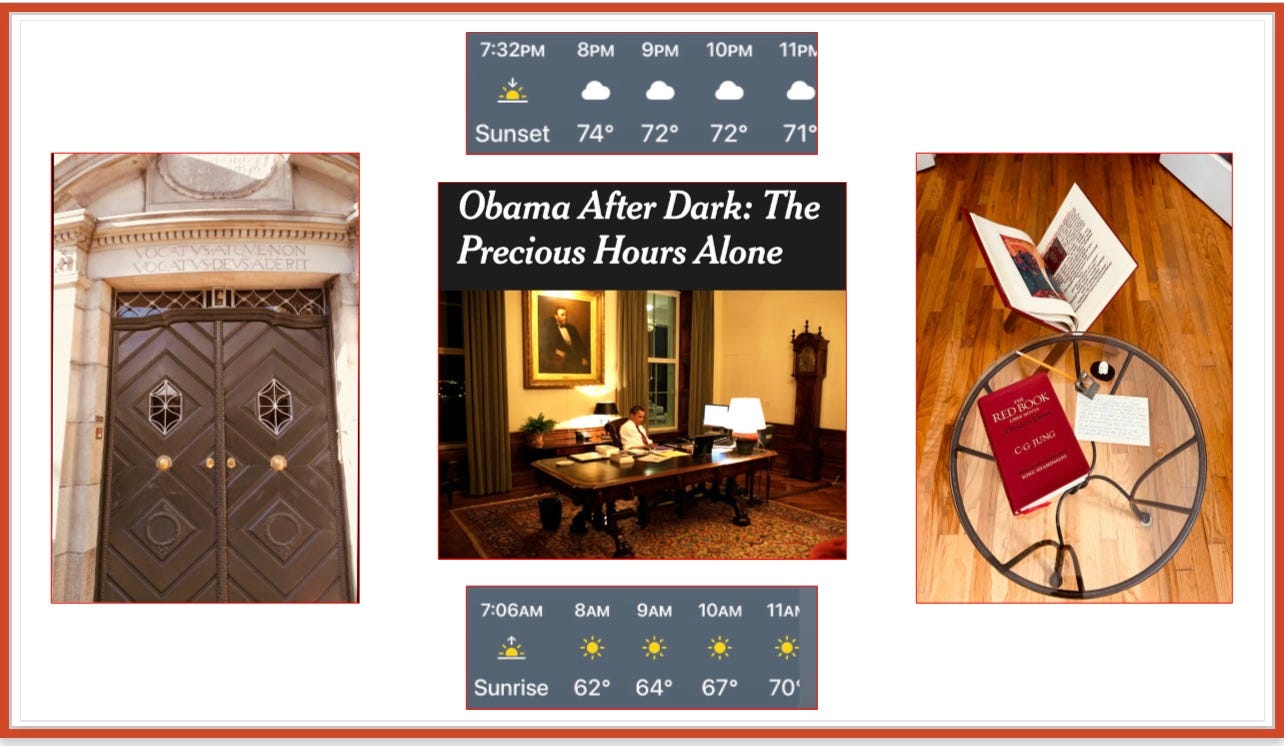

🔷 The current fast-waning daylight and longer nights (illustrated above center) brought to mind the saved-and-savored 2016 photo and profile of then-President Barack Obama by Michael D. Shear. It captures an unusually personal dimension of him and his temperament a few months before leaving office. Then and even more today, I value these qualities as rare, if not unique, among leaders and public figures across our culture.

🔷 Then somehow this week, after unrelated topical newShrink browses of The New York Times, into my inbox came a long, never-seen NYT Sunday Magazine piece from 2009. It was an in-depth announcement of the retrieval and first publication of Jung’s long-privately-locked-away, in-every-way-gigantic, illustrated personal journal, The Red Book.

Nothing about the re-posted article in my email emphasized the date as an anniversary. The September 20, 2009 publication date just happens to have been 14 years ago this Wednesday. (That was during my Pacifica grad-school years. I think my back-ordered first-printing copy wound up being a Christmas gift that year.)

🔵

Obama After Dark: The Precious Hours Alone

(By Michael D. Shear. Quoted excerpt from The New York Times, July 2, 2016)

This first 2016 piece about then-President Barack Obama brings such immediate recall of the amazingly reassuring power evoked by his calmly thoughtful intellect, warmth and steady hand on the wheel-of-state. The contrast with the wounding years that have followed is so great that this next section may warrant an excruciating-nostalgia trigger warning.

Mr. Obama calls himself a “night guy,” and as president, he has come to consider the long, solitary hours after dark as essential as his time in the Oval Office. Almost every night that he is in the White House, Mr. Obama has dinner at 6:30 with his wife and daughters and then withdraws to the Treaty Room, his private office down the hall from his bedroom on the second floor of the White House residence.

There, his closest aides say, he spends four or five hours largely by himself. He works on speeches. He reads the stack of briefing papers delivered at 8 p.m. by the staff secretary. He reads 10 letters from Americans chosen each day by his staff. “How can we allow private citizens to buy automatic weapons? They are weapons of war,” Liz O’Connor, a Connecticut middle school teacher, wrote in a letter Mr. Obama read on the night of June 13. The president also watches ESPN, reads novels or plays Words With Friends on his iPad.

Michelle Obama occasionally pops in, but she goes to bed before the president, who is up so late he barely gets five hours of sleep a night.

“For Mr. Obama, the time alone has become more important.”

“Everybody carves out their time to get their thoughts together. There is no doubt that window is his window,” said Rahm Emanuel, Mr. Obama’s first chief of staff. “You can’t block out a half-hour and try to do it during the day. It’s too much incoming. That’s the place where it can all be put aside and you can focus.”

Staffers interviewed describe how they knew they’d come in to completed responses and notations in margins every morning — about every item in the daily briefing book.

“A lot of times, for some of our presidential leaders, the energy they need comes from contact with other people,” said the historian Doris Kearns Goodwin, who has had dinner with Mr. Obama several times in the past seven and a half years. Ms. Goodwin goes on to say:

“He seems to be somebody who is at home with himself.”

The seven almonds.

To stay awake, the president does not turn to caffeine or junk food. He rarely drinks coffee or tea, and more often has a bottle of water next to him than a soda. His friends say his only snack at night is seven lightly salted almonds

“Michelle and I would always joke: Not six. Not eight,” Mr. [family chef Sam] Kass said. “Always seven almonds.”

Most of the latest or near-all-nighters were when Obama was focused on intensely important speeches that also had emotional and personal significance.

Then-presidential speechwriter Cody Keenan had worked in this wee-after-hours study with Obama on two of the more devastating and emotional speeches of the period:

One was his eulogy for nine African-Americans fatally shot during Bible study at the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, S.C. in June 2015. Another was Selma, Ala., on the 50th anniversary of “Bloody Sunday,” when protesters were brutally beaten by the police on the Edmund Pettus Bridge. Reflecting on his boss’s use of the time, Mr. Keenan said:

“There’s something about the night. It’s smaller. It lets you think.”

The time wasn’t all-work. And there were also sports and movie viewing and stress-relieving fun exchanges.

Some of my thoughts:

These ritual night-hours when President Obama wasn’t traveling were a time for reflection, recharging… and what psychologists call integrating experiences and thoughts, plus the important emotional and relational aspects.

There’s nothing here particularly esoteric, mystical or even overtly “psychological” or “mentally healthy.” But the story’s many elements speak to serious, even crisis-level issues and trends today. Just this week came the latest sobering results of extensive studies of dire impacts on our health, longevity, risk factors for debilitating illness and life-events — from loneliness. Yet as the pandemic taught us, Americans increasingly lack capacity and role models (such as Obama) for discerning debilitating loneliness from conscious solitude that is life-enriching and even -saving..

The temperamental personality pattern introversion itself is not only out of fashion currently, but dismissed or rebuked as pathological. Several draft versions of the 2013 most recent DSM revision had added introversion as a named disorder. In response to backlash the final version (at least for this round) backed off of the named broad category while adding more introverted tendencies under other disorders’ various negative descriptors.

There’s drastic need for the levels of mindfulness in decision-making that are essential for self-regulation of our emotional reactivity. Without that at individual and collective levels we are a nation nearing epidemic levels of operating in a state of perpetual fight-flight-freeze. As we see in the news cycle week-after-week, our collective reptile-brain is effectively in charge. That’s the case across so many arenas of our culture from politics and education to parenting, policing, gun violence and culture wars around race, sexuality and gender.

From a purely mental-health perspective at this point, we could all do well to have a commander-in-chief conducting morning mindfulness meditation and evening Tai Chi classes on the White House lawn.

🔵

Pictured at top left, now the doorway to Jung’s very different, also rich interiority.

“Bidden or unbidden, god comes in”

The header here is the translated Latin that Jung had inscribed in stone over the entry door to his Kusnacht, Switzerland, consulting room. He worked with his analytic psychotherapy patients there for some 50 years. This included the World War I period when at 38 in 1913 he began charting his “confrontation with the unconscious” that became The Red Book… and his analytical psychology. He and wife Emma, heiress of the wealthiest family in Switzerland at the time — also were raising their still-young five children.

For full disclosure I have hung out with the beautiful, near psychedelic book for 14 years. It’s been right alongside my own clinical practice and study of his and his successors’ large scholarly and often-brilliant clinical body of work.

As I consider how to describe or think about The Red Book today, in tone and purpose it has much in common with Dante’s Divine Comedy account of his own midlife plunge-into-abyss.

I’ve come to view and relate to The Red Book as Jung’e dream journal from an intense initiatory crisis period of his adult life. As such, over 100 years ago it might even have been the first such dream journal of the modern/post-modern era.

To research this long, very readable New York Times Sunday Magazine piece, starting in 2007 author-journalist Sara Corbett boarded a train for Zurich. For a long period afterward she clearly embedded among the Jungians, editor Sonu Shamdasani plus the more-than-prickly Jung family. All were quite different factions with not innately common interests in The Red Book’s prospects, or its very existence. (For those interested, Jung’s extensive, many of them exquisite, illustrations in the book are readily browsable,)

The Holy Grail of the Unconscious (New York Times Sunday Magazine, September 20, 2009, by author Sara Corbett.)

Along the way Corbett meets and shares great, at times inside-joke-funny, anecdotes. She points to some of the side-alleys and dark mental-rabbit-holes that seem inevitably part of any serious visit with Jung, his ideas and times. Historically and now, he has been a powerful lightning rod figure attracting enormous projections both idealized and demonized. As with the nature of projections, the man himself was surely neither… and both.

All of this, in fact, is perhaps evidence of the very nature of the unconscious psyche to which he devoted exploration over the next 50 years of his professional life.

For those interested, the award-winning biographer Deidre Bair’s 2003 volume is the definitive scholarly, non-hagiographic, biography of Jung; I highly recommend it.

Here, Corbett’s apt take on some common Jungian quirks made me chuckle:

…there are a lot of Jungians involved, a species of thinkers who subscribe to the theories of Carl Jung, the Swiss psychiatrist and author of the big red leather book.

“Jungians, almost by definition, tend to get enthused anytime something previously hidden reveals itself, when whatever’s been underground finally makes it to the surface. “[!]

[A note here: In practice and preference Jung reportedly went by C. G., not his first name.]

(Corbett):

Jung founded the field of analytical psychology and, along with Sigmund Freud, was responsible for popularizing the idea that a person’s interior life merited not just attention but dedicated exploration — a notion that has since propelled tens of millions of people into psychotherapy.

“In order to grasp the fantasies which were stirring in me ‘underground,’ ” Jung wrote later in his book Memories, Dreams, Reflections, “I knew that I had to let myself plummet down into them.” He found himself in a liminal place, as full of creative abundance as it was of potential ruin, believing it to be the same borderlands traveled by both lunatics and great artists.

Jung recorded it all. First taking notes in a series of small, black journals, he then expounded upon and analyzed his fantasies, writing in a regal, prophetic tone in the big red-leather book. The book detailed an unabashedly psychedelic voyage through his own mind, a Homeric progression of encounters with strange people taking place in a curious, shifting dreamscape. Writing in German, he filled 205 oversize pages with elaborate calligraphy and with richly hued, staggeringly detailed paintings.

What he wrote did not belong to his previous — or subsequent — canon of dispassionate, academic essays on psychiatry. Nor was it a straightforward diary. It did not mention his wife, or his children, or his colleagues, nor for that matter did it use any psychiatric language at all. Instead, the book was a kind of phantasmagoric morality play, driven by Jung’s own wish not just to chart a course out of the mangrove swamp of his inner world but also to take some of its riches with him.

It was this last part — the idea that a person might move beneficially between the poles of the rational and irrational, the light and the dark, the conscious and the unconscious — that provided the germ for his later work and for what analytical psychology would become.

The book tells the story of Jung trying to face down his own demons as they emerged from the shadows.

He worked on his red book — and he called it just that, The Red Book — on and off for about 16 years, long after his personal crisis had passed, but he never managed to finish it. He actively fretted over it, wondering whether to have it published and face ridicule from his scientifically oriented peers or to put it in a drawer and forget it.

Regarding the significance of what the book contained, however, Jung was unequivocal:

“All my works, all my creative activity,” he would recall later, “has come from those initial fantasies and dreams.”

Corbett thoroughly describes editor Sonu Shamdasani’s long process of first convincing Jung’s family to release the book for publication. Then began several years of tracking and annotation of extensive footnotes. She met with him soon after that:

[Shamdasani had] only very recently found his way out of an enormous maze. When I visited him this summer in the book-stuffed duplex overlooking the heath, he was just adding his 1,051st footnote to The Red Book.

The footnotes map both Shamdasani’s journey and Jung’s. They include references to Faust, Keats, Ovid, the Norse gods Odin and Thor, the Egyptian deities Isis and Osiris, the Greek goddess Hecate, ancient Gnostic texts, Greek Hyperboreans, King Herod, the Old Testament, the New Testament, Nietzsche’s Zarathustra, astrology, the artist Giacometti and the alchemical formulation of gold. And that’s just naming a few. The central premise of the book, Shamdasani told me, was that Jung had become disillusioned with the limitations of scientific rationalism — what he called “the spirit of the times” — and over the course of many quixotic encounters with his own soul and with other inner figures, he comes also to know and appreciate “the spirit of the depths,” a field that makes room for magic, coincidence and the mythological metaphors delivered by dreams.

“It is the nuclear reactor for all his works,” Shamdasani said, noting that Jung’s more well-known concepts — including his belief that humanity shares a pool of ancient wisdom that he called the collective unconscious and the thought that personalities have both male and female components (animus and anima) — have their roots in The Red Book.

This description from Shamdasani points to my recent description of Jung’s decades-long collaboration with physicist Wolfgang Pauli and of his as a quantum psychology. Jung most definitely valued and built on both the medical psychiatry of the day and Freud’s psychoanalysis grounded in personal developmental experience in childhood.

First Freud, then a few years later Jung, were both in the early 1900s fairly lone pioneers of the unconscious mind. Rather than incarcerating and labeling “mental patients,” each dared to look at the inner felt-experience of people suffering psychologically. Going first, the elder Freud focused and made most of his earliest discoveries about unconscious functioning by working with highly repressed women during the Victorian era. They suffered from a range of many symptoms, often physical, but that were then called “hysteria” though their suffered symptoms were quite real. (The term hysteria is no longer a diagnostic term today in medical mental healthcare. But dismissal of similarly real somatic symptoms stills occurs quite often — especially with female patients.)

Through his own psychological crisis at mid-career and -life — ironically triggered in part by his devastating rift with his mentor Freud — Jung went a step further. He became a journal-ist in the original earliest sense of the term: He made the exploratory journey into his own unconscious, making notes and drawings in order to return and tell about it if he could. (In this, he’s more accurately compared with Dante Alighieri and his Divine Comedy than with Freud and conventional psychologists of the era.) Also in common with Dante, once experienced, the journey was the sort which cannot then be un-seen, unknown. The permanent chasm with Freud illustrates this. Painfully.

In addition to Jung’s expanded — I think hugely important — view of the unconscious as collective as well as individual, he makes another quantum leap beyond Freud and his followers. Jung finds that the unconscious is unlimited, and exquisitely so — never even possibly “drained” of its contents and images through analysis. Related to this, in Jung’s view the unconscious is forever pulling us energetically and purposefully toward integration of past and present with the future. This is beyond and in stark contrast to Freud’s past-focus on solely personal experiences in childhood.

In this way Jung’s analytical psychology is teleological. As such it’s a psychology and world-view better equipped to be big enough for the entirety of adult life, and lives, today.

My being far more a post- than pure Jungian (not to mention the deep journalism roots!) I valued this exchange between Corbett and Shamdasani.

(Corbett:)

“What about the rest of us, the people who aren’t Jungians?” I wondered. “Was there something in The Red Book for us?”

Shamdasani said, “Absolutely, there is a human story here. The basic message he’s sending is:

“Value your inner life.’”

Which rather brings this post full-circle…

🔵

Today I’ll leave you with the following text, brand-newly discovered for me this week. It joins my most treasured things from Jung — those regarding the sacred healing aspect of living in depth psychological process, particularly regarding dreams.

(Corbett)

Creating the book also led Jung to reformulate how he worked with clients, as evidenced by an entry Shamdasani found in a self-published book written by a former client, in which she recalls Jung’s advice for processing what went on in the deeper and sometimes frightening parts of her mind. Jung instructed her:

“I should advise you to put it all down as beautifully as you can — in some beautifully bound book.

It will seem as if you were making the visions banal — but then you need to do that — then you are freed from the power of them. . . .

Then, when these things are in some precious book you can go to the book & turn over the pages & for you it will be like your church — your cathedral — the silent places of your spirit where you will find renewal.

If anyone tells you that it is morbid or neurotic and you listen to them — then you will lose your soul.

For in that book is your soul.”

🔵

And, that is all I have! Talk to you next week.

🦋💙 tish

•🌀🔵🔷🦋💙

… it is important that awake people be awake,

or a breaking line may discourage them back to sleep;

the signals we give — yes or no, or maybe —

should be clear: the darkness around us is deep.

— William Stafford, “A Ritual to Read to Each Other”