Happy Friday, and welcome to another Shrink-wrap topic that has hijacked the week’s newShrink!

A news item and event last week piqued my interest along newShrink’s themes of both clinical and soul-focused psychology. Mike Collins of NPR affiliate WFAE’s Charlotte Talks had an excellent interview on Tuesday, October 5, with neuroscientist-novelist Lisa Genova, “The Science of Memory and Why We Forget.”

Queens University of Charlotte will host “An Evening with Lisa Genova” next Wednesday, Oct. 20, at 7 p.m. in the Sandra Levine Theatre at Sarah Gambrell Center for the Arts. (Many of Genova’s lectures and TED Talks are available virtually as well.)

Next week’s focus will again be News Notebook.An alternating rhythm is emerging here, with either a weekly deeper-dive, themed Shrink-wrap piece like this one or a broader cross-section of news and issues covered in the News Notebook — with the occasional abbreviated Postcard version as schedule requires. So email readers will continue to receive one post weekly, most always on Fridays. I’ll keep you informed as this evolves! (Anyone can also browse directly to the website anytime: newshrink.substack.com.)

connecting dots

This Shrink-wrap is an introduction to the intriguing Genova with some recap of her work. For me it’s also expanded as I’ve realized not only the subject’s clinical and current cultural-news implications, but that we are also talking about human consciousness and its vast potentials, capacity for movement forward, change, and deepening.

So it’s a story with appearances by some unexpected, seemingly unrelated topics and issues along with characters and their voices, ideas and works from current headlines, film, literature, music, depth psychology, and even an echo from 60s drug culture. All of whose relevance and connection I can only hope to make a bit clear here!

meet the neuroscientist…

While this show and event are local, the range of Genova’s work, impact and apparent creative thought is enormous. Here are highlights from her online biography.

“Genova graduated summa cum laude as valedictorian from Bates Coolege with a degree in biopsychology and earned her PhD in neuroscience from Harvard University.

Nicknamed ‘the Oliver Sachs of fiction and the Michael Crichton of brain science,’ she has an unusual niche in contemporary fiction, writing stories inspired by both neuroscience and a keen understanding of the human psyche.

Genova has written NYT bestselling novels Still Alice — adapted into the film for which Julianne Moore won the 2015 Best Actress Oscar for the title role — Inside the O’Briens and Every Note Played… and

Her most recent TED Talk, “How Memory Works — and Why Forgetting is Totally OK” was viewed over a million times in its first month. (Her first TED Talk, “What You Can Do to Prevent Alzheimer’s” has been viewed over 5 million times.)

She has been awarded the Pell Center Prize for Story in the Public Square.”

on our brains and memory…

In both her talk and the book’s first chapter, Genova directly takes on our widespread concerns over loss of memory with aging, risks and symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease. Describing memory and memory loss as occurring on a spectrum, she offers examples to help distinguish between normal forgetting and Alzheimer’s or other forms of dementia:

“Wait, I have it right on the” tip-of-my-tongue…”

This common syndrome is unlikely to be problematic or a symptom when the sought words or concepts are what she calls “cul-de-sac” nouns. Especially when they’re specific proper nouns like a name or a place, these are just part of slower processing speed with aging — I would add, even as some other functions like strategic thought are taking better hold.

Of greater concern is when common nouns such as “pencil” or “coffee cup” are not only forgotten but there’s no grasp of what they are for or the context for looking for them.

“Cul-de-sac words”

These are where we “circle the neighborhood” of our brain’s storage around and around for the familiar missing word, fact, phrase or idea factoid — and are normal.

Even better, Genova says research has demonstrated that Googling the answers to these kinds of pesky questions is not harming our — or our kids’ and grandkids’ — brains or capacity to remember things. In fact, it’s making time and space for new learning.

This is because in cul-de-sacs we’re just retrieving material we already have, not learning anything new, even once the missing word or idea is recovered. And in the half-hour or so spent searching for recall, the brain is not available for anything else. Says Genova:

“We can think of life as an open-book test, now!”

“Why did I come into this room?” or “Where did I park my car at the mall?”

NEITHER is a danger sign of Alzheimer’s or dementia.

Yellow or red flags arise when the questions, with increasing frequency, become things like “Where, or who, am I? What is a car? What is this place I am in, what is it for, how did I get here and why?”

Normal forgetting is a function of distraction, Genova explains. It’s all about paying attention — and forming the intentional habit of learning to do so. (So if you have a mindfulness, Yoga or prayer practice, GREAT.) This kind of “where did I park my car?” forgetting is a cue to slow down for a moment, stop thinking of and doing 15 things at once.

“The number one thing to lay down a memory in the brain is to PAY ATTENTION!”

(Perhaps my favorite “be curious” mantra from Ted Lasso can help with this.)

Summarizing on this, Genova says:

“The brain is terrible at thinking of things to do later, even just a little while later.”(So make lists, use them and try putting things down in the same place all the time, vs randomly.)

some of my thoughts

These issues of distraction and attention have big examples and ramifications in the both the current Facebook and Instagram discussions in the news and in the psychological, psychotherapy and soul dimensions of memory (the latter I’ll discuss more below.)

This month’s Facebook news, both regarding known impacts on teens’ brains and mental health and the broader issues of its largely unregulated influence across the population, touches on this distraction and attention issue involving our memory functioning. Psychologically it touches on the roles that mindfulness and intention — that “witnessing awareness” — play in our capacity to make true choices vs being driven by reactivity.

ADHD diagnoses and medication-treatment are an increasing trend in both children and adults, and there are links in strategy and treatment for both ADHD and working with trauma. (A useful resource on this is Dr. Gabor Maté’s Scattered Minds. This one’s recommended by a reader, dear friend and esteemed depth psychology educator/author I’ll share more about in future editions. Her priority-passion is individual psychotherapy practice deeply grounded in the depth traditions over a couple of decades, both in consulting room and virtual-remote nationwide and beyond.)

Even with cognitive behavioral therapy, a standard-of-care treatment modality to improve day-to-day functioning by reducing symptoms of depression and anxiety disorders, a key focus is training and practicing our ability to apply distractions to interrupt and disconnect thoughts and behaviors connected with painful feelings (and memories).

Our dominant culture (of which Facebook, Instagram and Twitter are representative expressions) intensely values and rewards patterns, habits and tendencies such as extraversion, speed, and action vs reflective thought. Consider, for example, that the national panel of esteemed experts in psychology, psychiatry and medicine reviewing and updating the most recently revised version of the DSM (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of psychological disorders, on which clinical practitioners must base their work) actually considered, and in earlier drafts came close to adding, introversion as a mental health disorder. Another pop-culture tool claiming neutral assessment of personality traits, not sickness or pathology, includes things called “agreeableness” and extraversion among its five markers defining a “healthy” personality.

One might well argue that a healthy dose of introversion — and even disagreeableness — might be a better idea, given near-epidemic levels of ADHD, anxiety and depression diagnoses, treatment and medication across all ages and subgroups in today’s America. The forced isolations of the lingering pandemic might even have been less psychologically debilitating had our collective “normal” not looked and felt so much like frenzy.

“flashbulb” and “episodic” memories

These are memories activated by powerful emotional triggers, either positive or negative, and tightly connected to context, story, meaning, physical and emotional responses.

Especially with such memories around an intensely negative episode, experience or event, Genova says,

“Your memory of what actually happened in a particular episode (particularly a negative one) is terrible!”

Two factors are involved here, one of which gets labeled and discounted as lying, but is more complicated. As illustration she describes researchers who interviewed many first-hand witnesses immediately after the 9/11 attacks and then asked them the same questions a month or two later. Almost no research subjects described anything similar to their first responses.

As Genova explains, the neuro-connectors across our brain, nervous system and the body’s emotional reactivity give extensive context to our memories. (Jung calls these emotion-laden, connected memories, our “complexes,” by the way.)

my thoughts

Those of us temperamentally and professionally oriented toward finding and honoring facts — especially having worked in or as journalists covering law enforcement, court proceedings, the sciences, or psychology — are familiar and well aware of the proven unreliability (and frustration) of eyewitness memory, story accounts or testimony, especially in stressful situations where emotional arousal is high. (And in these professions such high-arousal situations are often what make the individual newsworthy or otherwise the focus of needed attention.)

With any such experience involving high emotional arousal, the context (like a script, or a “set” in work with psychedelics) is disrupted. This can trigger a natural energetic (mostly unconscious) push for “re-enactment” — “replay, overlay and redefine the story” — response.

This might be understood as restoring order to chaotic exprerience. When going through it ourselves, we might experience it as effort to make of the memory new sense, meaning and story going forward.

And if the corrective re-enactment doesn’t and hasn’t occurred, the same powerful energies go toward stifling, “stuffing” or “burying” the memory.

Worth noting, this high reactivity and some of the “replay, overlay etc.” process happens, of course, with both intensely positive and intensely negative experiences of emotional arousal. We just don’t tend to notice, worry or obsess much about factual “accuracy” in our recall of the positive ones!

A vivid example of a “re-enactment” pattern is recent headlines regarding the traumatizing and depression-generating effects of unrestrained use of Facebook and Instagram by kids and teens. As even the company’s own research indicates, teens — especially girls — who are developmentally vulnerable to peer feedback and comparison, see and receive social media feedback or images that trigger negative feelings about themselves.

Because the urge by the brain, nervous system and embodied emotion to “replay in order to overlay a new (positive) story” is so great, the teens begin compulsively to return to the very virtual world where their wounding occurred. In this, largely unconscious, reactivity the teens are effectively re-traumatizing themselves.

(We adults, by the way, do a version of this same pattern when, rather than investigate and come to terms with our selves’ deepest patterns, we do things like date, marry or enter entangling work or friend partnerships with different people over and over who are replicas of abusing, wounding, cruel or neglectful caregiver or experiences from earliest, unconscious childhood.)

A second current and frequent news story example are teen and child sex-abuse cases, often pursued only long after the trauma that is experienced and can only be processed or treated as memory. Memory is at the core of all soul-focused psychotherapy work, and this example underscores how vital it is for the deep work of healing acute trauma, PTSD and the buried griefs of life.

It’s paradoxical that this same “factually unreliable memory” with its “re-enact, re-experience in new and safe context, and overlay of new story” by the brain, body and nervous system in response to highly emotional experience is also hugely adaptive.

It’s like a push on the part of both the conscious/cognitive and unconscious/soul areas of the brain and body to “correct” and heal the wounding experience. (In the Jungian depth psychological view, this is part of the constant movement of the energy of the unconscious soul/psyche — its libido — toward healing, integration, and our wholeness.)

So the telling, retelling, overlaying forward and looping back of different elements of story and memory, are at the heart of psychotherapy process —which at some point for individuating adults involves healing old grief. The re-enactment work is also most effective and permanent, if not essential, with acute- and PTSD trauma — especially when augmented by such neuroscience technology tools as EMDR (eye movement desensitization and reprocessing) and adaptive information processing.

Important to keep in mind, especially as so many coping strategies and even treatments in today’s world can sidestep rather than probe memory, the re-enact, re-experience and move the new story forward process is more difficult work with memories that have been long denied and buried. (Most difficult of all is with developmental — childhood — trauma where often the memory experience was when the child was pre-verbal or not yet at a level to process it cognitively at the time.)

much-coveted “cognitive reserve”

Genova highlighted the capacities that all of us retain even into advanced age — or with dementia — in our areas of deeply developed and long-established expertise.

She cited the heartwarming recent CBS 60 Minutes interview and story on the return-stage performance with Lady Gaga by 96-year-old singer Tony Bennett, who has advanced Alzheimer’s disease. (The program is browsable on You Tube.)

Bennett’s ability to perform, succeeding at recalling a surprising majority of lyrics and melody, demonstrates two other aspects of the memory-retrieval process. Along with our sense of smell, both music and lyrical verse are powerful stimulants and triggers. These can be useful not only for recovering material lost to dementia but also in the re-enactment, re-experiencing, overlay of one’s story going forward.

Genova closed with intense emphasis on good, long regular sleep… daily exercise… weight control… and healthy Mediterranean diet for optimal brain and memory health.

my thoughts

A note on establishing and “laying down in the brain and nervous system” the effects of healthy sleep, exercise, diet and stress-management: Many of the coping mechanisms and habits established over decades of adult life — including all of these areas as well as side effects of many kinds of medications — can themselves interfere with efforts to begin healthier regimens. The more, and earlier, these habits are a first, rather than added, priority, the better and quicker the effects on overall well-being.

With building cognitive reserve, too, some paradoxical current trends, practices and patterns can work against the very memory-health and resilience we desire. For example, clinical methodologies such as Rx for depression and anxiety — which are definitely needed when even everyday basic functioning is a challenge, or impossible. Yet it’s important to be aware that, especially over long-term use, both standard medication categories have well-documented cognitive impacts and memory-retrieval impacts.

Antidepressants— standard of care for both depression and chronic anxiety, to assist with the painful ruminating thoughts-feelings spiral common to both — actually work in the brain by helping to interrupt the associative connectors that put together the story of memory/ies. So over time, we are functioning by “not thinking so much about it,” by not focusing on the memory-story/ies or creating/overlaying new ones.

Even with mindfulness-based cognitive behavioral work, a primary focus is training the brain and behaviors to distract from painful thoughts and feelings. So over a long period of time, although unintended consequence, the focus of treatment has effectively been on not remembering.

Another trend is the very common prescription and long-term use of anti-depressants and anti-anxiety medications from our primary-care doctors, without accompanying “talk” psychotherapy to uncover and deal with the layers of memory behind the symptoms. (The best, depth-focused psychotherapist will likely begin treatment work with a caution that sounds something like, “you are probably going to feel a lot worse awhile, before you begin to feel better.”)

Similarly, the standard anti-anxiety medications (often also, with less than optimal results, prescribed for insomnia) — such as benzodiazepines like Xanax, Valium, Klonapin — have cognitive and memory impacts that are well-documented in clinical studies as long-term in the over-50 population with regular use that lasts longer than 90 days.

All of these medications are useful, even essential, to relieve symptoms and suffering that can make day to day functioning, and even life itself, intolerable or impossible. How they work, and potential resulting effects, are simply factors in considering optimal memory functioning over the long term.

If taking and needing to take them, it makes sense to add as a high priority some mitigating elements too, such as good talk therapy, regular regimen of healthy sleep hygiene, daily exercise, and diet for brain health.

Meanwhile, I see many hopeful prospects and future frontiers for this aspect of human consciousness and healing. One exciting example, which I was fortunate to learn about at an international depth-psychologist conference awhile back (before COVID), are new research studies and controlled-experiment tests using psychedelics such as psilocybin and LSD in many psychotherapeutic, psychiatric and neurological ways.

The excellent journalist Michael Pollan — whom you may know best for his explorations of food with The Omnivore’s Dilemma and In Praise of Food — has researched and written an exhaustive history and presented the field’s vast potentials in his book How to Change Your Mind. Clinical uses of special interest and apparent effectiveness include treatment of acute- and post-trauma, end-of-life grief, depression and anxiety, and alcohol addiction — as well as exploration of human consciousness by some.

Meanwhile, no discussion of memory would be adequate (or much fun) without a few of the many cultural examples and functions of memory retrieval, re-enactment, overlay of new and meaningful story and the like, in film, song, and literature.

“you must remember this”… about that song

If you’re familiar with Casablanca you’ll recall that it has pretty much the ultimate in tragic wartime love story endings, complete with lines that are indelible cliches for generations of us. (That sad ending, and the mostly unconscious urge to re-enact and “fix” it, probably has a lot to do with how well so many know and remember the film as such a classic.)

This psychologically hard-wired urge to re-enact, re-experience in order to overlay and re-create our unique story forward, also might explain the appeal of so many sequels in film, theater and literature. (I’m not sure a Casablanca one is even imaginable, or if I’d want it to be. But I’d sure pay $ to see a decades-later sequel to the Tom Hanks film Castaway! At least maybe he’d get a new beloved Wilson volleyball.) And yes, I had to Google that…

Genova describes the neuro-connection context for how memory is stored and retrieved in our minds. (I say “minds,” for memory involves the entire nervous system and the body’s stored emotions and limbic system as well as the brain.) I envision this as more like an archaeological excavation, a dig down through layers as well as broadly, vs just opening a file drawer and sorting folders.

With this excavation — in both my long clinical practice and my personal experience working with memory — each “uncovering” and pulling up of a memory and integrating it in conscious awareness then allows and reveals new one(s) that had been buried, kept unconscious, beneath it. These fresh, newly claimed memories, appearing once a long-embedded, heavy one has been moved, are almost always erotic-energetically alive, often welcome happy surprises after painful labor of “moving” a heavy one.

This “excavation” as well as the re-enactment process suggested by Genova’s work illustrate Jung’s view that the unconscious is infinite, with new personal and collective contents always moving to the surface as we attend to what has emerged in our awareness. Jung, and Jungians, also view this as a positive thing: the energetic push of the soul or psyche ever forward toward wholeness.

This is in contrast to Freud’s view that the unconscious/soul is comprised only of each individual’s past experiences, traumas, feelings, relationships with caregivers and significant others from our infancy. Freud and Freudians believe that with enough analysis the entire contents of the individual’s unconscious could be “emptied,” brought to conscious awareness. At which point, Freud famously — and depressingly — said: All of our neurotic sufferings are transformed into ordinary misery!

I’m reminded here of the question New York Times columnist David Brooks asked with the title of a recent piece (shared in last week’s News Notebook) highlighting his periodic efforts to define, somehow pin-down and “resolve” what the self is.

His title question: “Is self-awareness a mirage?”

I wind up saying both “yes,” and “not exactly.” I believe Brooks is trying to talk about the capital-S or Soul-engaged self, and yes, the unconscious pulls us forward, ever-beckoning us toward and further “into it.”

But my “not exactly” arises out of that image that it’s more like an archaeological dig, where there’s unearthing and revealing of the new that had been obscured until material “above it” was pulled up.

Having read Brooks on his psychological and spiritual journey, including his books, for a long time I have long hoped for him an eventual shift he seems to be craving — to a more forward-moving energetic focus of the Jungian and post-Jungian end of the depth psychology spectrum.

Brooks has clearly done, and written about, a lot of work and exploration of the human (and his own) psyche. The emphasis has clearly been on dynamics of childhood and past attachments, relationships and causations into the present, and current popular treatment approaches — all of which is valid and useful foundation. He now seems to keep circling back to similar questions he tries to “nail down” using his excellent journalist skills and what appears to have been a whole lot of Freudian and post-Freudian depth analysis. To me Brooks has long seemed poised for a quantum leap I hope he makes — and writes about!

two closing voices

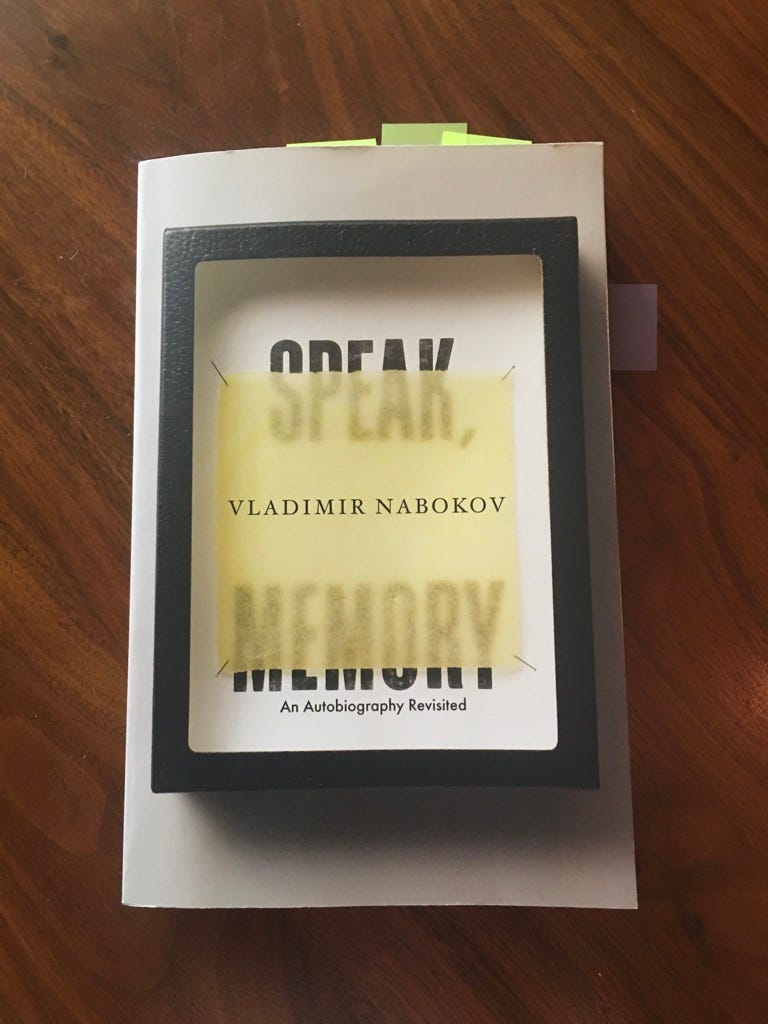

A casual revisit to this long-loved and familiar memoir, given today’s title subject of Memory, yielded a couple of happy surprises with a passage in one of the book’s closing chapters.

Here I hadn’t recalled Nabokov’s image of the “spiral,” which is one that depth psychotherapists often envision and use to describe the re-enactment processing of memory in the consulting room of psychotherapy. Also, Nabokov’s references here to Hegel’s “thesis/antithesis/synthesis” concept almost eerily echo Jung’s descriptions of our selves’ creative individuation over the course of life by “holding the tension of the opposites” in order that a “transcendent third” can emerge:

“The spiral is a spiritualized circle… A colored spiral in a small ball of glass, this is how I see my own life. The 20 years I spent in my native Russia (1899-1919) take care of the thetic arc [Hegel’s thesis]. Twenty-one years of voluntary exile in England, Germany and France (1919-1940) supply the obvious antithesis. The period spent in my adopted country [the U.S.] (1940-1960) form a synthesis — and a new thesis.”

🦋💙

Bringing a second closing note, the late poet-lyricist Leonard Cohen.

Here’s where Cohen’s years-long process, with this one song, so evokes the unfolding “re-enactments” and overlay of memory.

“When he began to work on ‘Hallelujah,’ he kept writing verses, filling notebooks with perhaps 180 of them, and the song literally took years to complete. Cohen didn’t do this with other songs. It’s as if he knew that with ‘Hallelujah’ he wasn’t just writing a song but birthing it. Yet part of the alchemy of ‘Hallelujah’ is that, over time, the song it turned into isn’t the one that it started out as. The song took a journey — changing, becoming, acquiring layers of soul and enchantment.”

And, that is all I have. Talk to you (and more briefly) next week!

🦋💙tish

… it is important that awake people be awake,

or a breaking line may discourage them back to sleep;

the signals we give — yes or no, or maybe —

should be clear: the darkness around us is deep.

— William Stafford, “A Ritual to Read to Each Other”

Nothing specific here, but I get the heebie-jeebies (look for it in DSM-6) when I see the conversation skating toward "recovered memories".... Lots of innocent defendants have been imprisoned by baseless claims of sexual abuse pried loose by overreaching therapists. Fortunately the worst seems to be behind us, thanks to a few multimillion-dollar damage suits .... https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/ct-xpm-2004-02-13-0402130313-story.html

Hi, Lew -- and I'm glad you commented here; I was actually thinking of you (and a lot of your deep interest and important work around this important -- and totally valid dimension of this.) It's a thorny, complex issue and process where the complexities of the truth are of life and death importance.

From still another facet of this, totally outside the therapeutic or the legal contexts, one of the devastating discoveries of my adult life, close friendships and business relationships with tremendously accomplished and "high-functioning" people... for whom very thoroughly recalled, and all too true, day-to-day (and nighttime) realities of unspeakable childhood and teen abuse were their "normal" fact of life. I'm astounded anew all the time by what each of us carries around, still not only functioning but doing good things.

We humans and the psyche are complex, both sacred and profane for sure.

Thank you so much for reading, and for sending over your wonderful-ness in so many ways.