Greetings from this surreal whiplash of a news-scape week.

It’s the first in a while that’s called up newShrink’s wind-spitting purpose and labor-of-love origins… as title themes!

I had been immersed in sorting voluminous finds for this series of man-in-the-movie shrinkwrap posts as introduced last Sunday, featuring a depth psychological take on Oppenheimer.

“Oppie”

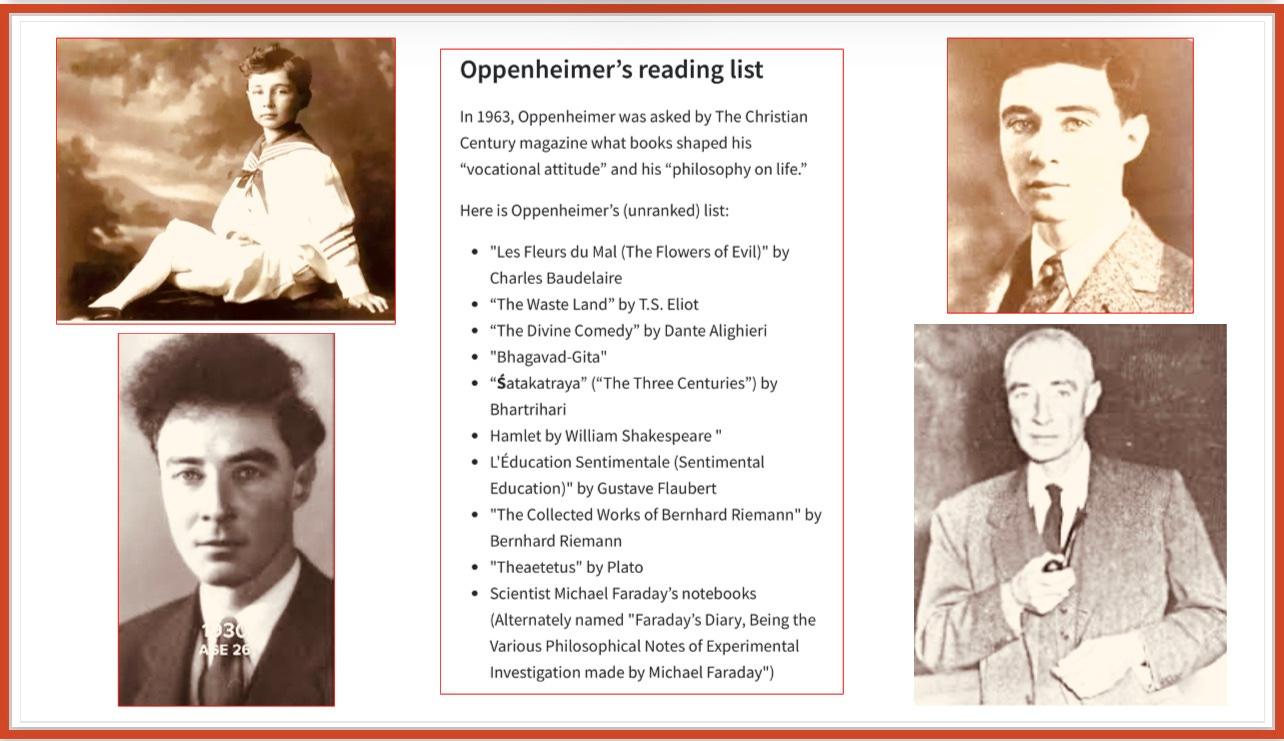

Pictured at center above are perhaps my two favorites among dozens of explored anecdotes, memorabilia and photos of J. Robert Oppenheimer, “Oppie.” By all accounts, his love Jean Tatlock coined the affectionate (not to mention blessedly briefer) nickname soon after they met and connected at Berkeley in 1936. It stuck for the rest of his life. For me the above blackboard photo of him captures inquisitive, alert intellect plus something movingly open and vulnerable. (No esoteric psychologizing on this, purely personal projection!)

Below it Oppenheimer's copy of "Bhagavad-Gita," translated by Arthur W. Ryder, for me rather begs to be touched. It’s part of collections at the Los Alamos Lab's Bradbury Science Museum. Oppenheimer's handwritten initials appear in the upper right corner of the front endpapers. The book is one of just two of his personal items that the lab owns, the other being his office chair.

Then, this…

🔵

Firestorm Furies

Dominating news reports were Maui wildfire devastation and dramatic Georgia grand jury indictments arriving late Monday. (Both stories illustrated at above right.) The stunning 41-felony-count racketeering indictments charge Donald Trump and 18 codefendants as a criminal enterprise, alleging they conspired to overturn the will of the voters in the not-close, fairly decided 2020 presidential election.

Across screens came reruns of a TV news video-clip from a year ago. It caught my ear when an irate U.S. Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.) seemed to be snarling about Greek mythology. But no. The passionate Trump-loyalist senator merely relied on myth-as-sound-bite-cliche to threaten dire consequences and lambaste “opening of Pandora’s Box” via prosecution of a former president through due process based on consideration of substantial evidence.

Back to this…

🔵

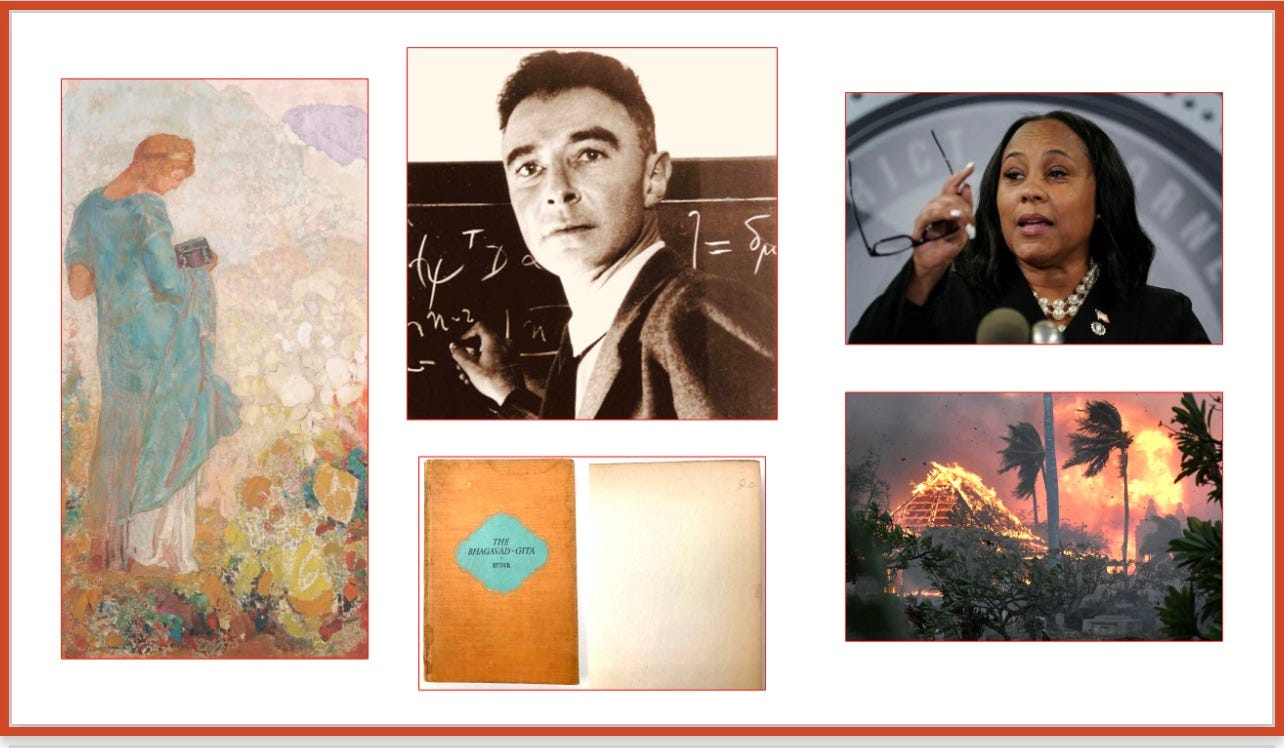

Pandora: Painting by Odilon Redon, National Gallery of Art

(Pictured above left.) As it happens, Pandora plays a significant role in the unfolding archetypal story of mythical Prometheus. He’s the alleged fire-stealing Greek titan so widely associated in metaphor and titles with Oppenheimer as so-called “father of the atomic bomb.” (In shortest recap of the myth, the issue was Prometheus’ use of the fire with which he had previously helped fellow-god Zeus, and still had. Prometheus used the fire for the service and benefit of mere mortals, humankind, rather than as continuing tribute to powerful Zeus. This so provoked vindictive Zeus’ wrath that years of punishing, relentless torture ensued for Prometheus — relieved only by the gift of his foreseeing/foretelling the future, albeit eventual and distant, release.

Both Prometheus and Pandora figure prominently in this look at Oppenheimer psychologically through archetypal lenses. With Pandora we have the familiar audacious, yet elusive, hope remaining in the vessel following forbidden release of all human ills on the world.

Meanwhile, news updates return next week. And larger issues in both the Trump criminal cases and wildfires merit, and will have, focus in later editions.

NOTE: This is an unusually long post that’s pretty unavoidable. Let me know if you need me to re-send yours individually in a couple of smaller separate emails. (There’s a reason I don’t do longer-form shrinkwrap pieces often — whew!)

🔵

From the movie…

Response to Christopher Nolan’s well-timed recent release of Oppenheimer has only begun, the film widely acclaimed as a masterpiece of scope, complexity and technical excellence. No celebratory midsummer-romp of a blockbuster, the film disturbs, provokes, at times paralyzes. Its war- and post-war scope and historical documentary aspect, with so much relevance today, are well-mined material elsewhere. The newShrink focus is the movie as psychological-biography.

As mentioned last week, from a depth-psychological viewpoint the film’s capture of the interiority within and between these characters is breathtaking. In one such moment early in the movie, we experience some of the young physicist’s flying-leap firing of cerebral synapses through rapid-fire technical flashes.

Intimate scenes between Oppenheimer and Jean Tatlock — by many conventional measures a pairing of two unique, if not strange, individuals who found and got one another — are another example. A psychological technique I like in the movie is the periodic, matter-of-fact inclusion of characters’ onscreen mental-pictures of their interior felt-experience of the situation. As viewers we’re being given both objective/outside-in, and subjective/inside-out views of the same scene at the same time. Its very jarring quality underscores that inner-outer cognitive disonance. Scenes during the intensely emotional security-clearance-removal hearing are another example.

A depth-psychology teaching tool?

Such awareness and attention to interior life, the felt experience — even/especially our own — is alien, largely unmapped and unguided terrain in today’s prevailing psychological mindscape. That gives the movie a rare other dimension aspect usually reserved for sci-fi and fantasy genres, rather than biopic.

It’s also what the psychologist in me, right alongside the journalist, likes best about it.

Nolan, and presumably his producer-partner wife Emma Thomas, have expanded conventional cinematic norms here to bring psychological intelligence, maturity and depth to the screen. If it isn’t already, Oppenheimer, the movie, belongs in the clinical and analytical training classrooms as a teaching tool for therapists of every theoretical persuasion and client-population focus, everywhere.

🔵

How do we know? The sources

Here, as for the movie, the definitive biography and primary source is American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J.Robert Oppenheimer, by the late Martin J. Sherwin and Kai Bird.

With the two collaborating to complete 20+ years of exhaustive research by atomic-era history professor-scholar Sherwin, the book won the 2005 Pulitzer Prize and 2006 National Book Critics Choice Award.

In one of this story’s many ironic notes alongside its themes of mutliple tragedy, 84-year-old Sherwin’s 2021 death with cancer was on the same day the two authors received news that Christopher Nolan was adapting their book as a movie.

With the film’s release, promotional interviews and articles have also (to their credit) largely quoted the biography. Their many duplicataions and overlaps are summarized, and quotes from specific individuals are cited or linked in the text. Some excellent timelines and biographical details also came from official websites at the Bradbury Science Museum at Los Alamos and Atomic Heritage Foundation.

The New York Times provided a helpful guide to the movie’s characters, though with more emphasis on professional than personal spheres.

Here’s a gem in Oppenheimer’s own words, with thanks to reader and near-lifelong friend Pam McMahon Miller, who pointed it out online. Based on his long friendship and collegial work in Princeton with Albert Einstein, Oppenheimer delivered this as a lecture at UNESCO House in Paris on December 13,1965. Beyond the complex physics, it’s a wonderful glimpse of Einstein’s humanity and captures the warmth between them:

Robert Oppenheimer On Albert Einstein (March 17, 1966 issue of the New York Review of Books).

And now

… the man

In a caption to the top left child-photo above, Oppenheimer is described from an early age as prodigy and polyglot. In adulthood he’d mastered seven languages: English, Greek, Latin, French, German, and Dutch (which he learned in six weeks to deliver a lecture in the Netherlands — as shown in the movie). All in addition to Sanskrit, for which he had audited classes at Berkeley in spare time to learn years before the war in order to read the Bhagad-Gita text he so valued in its original language. As with his Jewish heritage, he was not a religious Hindu.

Biographical highlights & timelines: Oppie, 1904-1967

J. Robert Oppenheimer was born in New York City April 22, 1904, to non-religious German-immigrant Jewish parents working hard to assimilate among rising upper middle class. Early educated in the Ethical Cultural School and valedictorian of his high school class, he enrolled at Harvard in 1922. This was just as Harvard began limiting the number of Jews admitted, as did other American and the similar elite institutes of science and academia throughout Europe.

Between 1925 and 1936: The near-entirely apolitical, nonreligious Oppenheimer did graduate work in physics in England at Cambridge; finished graduate studies in Gottingen, Germany, under (also Jewish-born) Max Born to earn his PhD in physics there. Returning to the States in 1927, he joined the faculty at Caltech and Berkeley (which in the movie is where we meet him, Jean Tatlock and others more closely, in 1936.)

With still-isolationist, Depression-stricken America years away from involvement in World War II, Oppie’s growing awareness and concern was not politics or religion but his fellow-scientist European friends and former classmates. So many of them Jewish, all under escalating risk of violence, incarceration and ultimate annhilation. Thereafter throughout his career, Oppenheimer intentionally hired and staffed his labs and faculty from among the many available well-qualified Jews. His never being a religious or much identifying as a Jew harmed him gravely later, as the movie explores with Strauss’ vendetta and ultimate betrayal.) But Oppenheimer had deducted from his pay regular financial support for Jews facing high risk.

In 1936: By then a well-established and popular thinker and professor at Berkeley, 32-year old Oppenheimer met and added Jewish-born physicist Robert Serber as his staff assistant. Their professional association and closest personal friendship would endure through Oppenheimer’s 1967 death. Unlike still-isolationist America, in Europe the Spanish Civil War is beginning. Defenders of the democratically elected government of Spain (supported by the Soviet Union) were fighting the powerful military and wealthy junta under Franco that had overthrown it (supported by Nazi Germany).

As depicted in the movie, this was where Oppenheimer met Jean Tatlock, the 22-year-old daughter of his fellow popular Berkeley professor-friend, whose own field of expertise was philology (study of languages) and classical literature. More like scientist Oppie than the Dad she idealized, Jean was a brilliant Stanford medical student in psychiatry (in the field’s predominant Freudian mode of the day). A supporter of the republican-democracy cause, she joined the Communist Party USA (which Oppenheimer never did) and wrote as a reporter for its Western Worker newspaper. But Tatlock also met, shared and by his own account instilled in Oppenheimer her deep knowledge and passion for literature, drama and arts. This included her beloved John Donne, T.S. Eliot and others who became his lifelong favorites.

The above-center photo of Oppie’s reading habits is among great material from this good read on the Los Alamos National Laboratory website: Plutonium and poetry: Where Trinity and Oppenheimer's reading habits met.

Here the movie picks up and fairly presents both Oppenheimer’s escalating Manhattan Project in professional life and key personal relationships. (Timelines on his official biography websites omit the personal entirely on him, though not those of women and children important to him.)

So theirs are next here.

By way of caution:

The next two photo-illustrated sections have discussion of 3 suicides, including that of Jean Tatlock as portrayed accurately and sensitively in the movie. Another was the publicly and historically known, physician-assisted, family supported death of 83-year-old Sigmund Freud in September 1939. It’s relevant here due to the time period and Freud’s tremendous psychological influences on Jean Tatlock, who was a medical student, then a Freudian MD psychiatriast, whose rigorous training had required long personal psychoanalysis with a Freudian.

Tatlock’s tragic death, January 4, 1944, was after widely reported long struggles with depression so severe that she actively sought treatment for it at Mount Zion Hospital (where she was also a psychiatrist). In personal correspondence, with Oppie and presumably in her own Freudian analysis she struggled with what to make of erotic feelings she had toward women alongside those toward men. There was intense pressure from the era’s enormous near-universal societal prohibition and stigma regarding same-sex attraction and relationship. More horrific to imagine is the inherent pathologizing and inescapable shame she’d likely have experienced under the prevalent application of Freudian psychoanalytic theory of the day. Among much that would merit unpacking: Tatlock’s bigger reported attachment was to her father, and her mother died in 1937. This was just as her intense love relationship unfolded with the compelling mutifacted Oppie, whom she greatly admired like her father… but who by all accounts both accepted and adored her. (On discovering her suicide when checking on her welfare, her father first burned her personal letters and journals before calling to report the death. It seems things about the daughter he loved were unacceptable to him. At the time, this behavior added fuel to speculation — somewhat believed even by her brother — that Tatlock had been killed by government agents because of her communist ties. However, she had left an authentically verified suicide note.)

The loss of gifted, dynamic Tatlock just short of her 30th birthday, during a stormy historic moment, is indescribably tragic. Especially given her profession as a psychiatrist, in addition to effective therapeutics I wish that she had had a belief system large, deep and compassionate enough to hold and nourish all that she was and could have become.

If suicide is a present concern for you or loved ones, along with recommended help with therapist, doctor, or clergy, 988 is the phone or text emergency hotline.

During her short, vibrant life Jean Tatlock (at left) is first up here, as she was first chronologically. She was also Oppenheimer’s first, at least twice-bethrothed, choice of life-mate during their passionate, turbulent relationship between 1936, their final time together in summer 1943 depicted in the film, and her death in January 1944.

Tatlock was born in Ann Arbor, Michigan, February 21, 1914, the daughter of John Strong Perry Tatlock and Marjorie Fenton Tatlock. John Tatlock was a prominent Old English philologist and Chaucer expert. From him she developed a shared love of literature, arts and drama even as her excellence in science drew her to medicine. Her older brother Hugh also became a physician. After graduating from Vassar College in 1935 she earned her degree in Freudian psychiatry from Stanford Medical School and completed her residency at Mount Zion.

Jean was Robert’s truest love; he loved her the most, was devoted to her. The pair were an item and something of an intellectual power couple. There was Jean’s popular professor-dad, Oppenheimer was the star of the physics department, luring talent from all over the nation to join him. Tatlock was a trailblazing Freudian psychiatrist who delighted Oppenheimer with her love of poets like John Donne.

In the biography another friend recalled that “all of us were a bit jealous.”

From interviews with director Nolan about capturing this significant relationship in the film’s few brief scenes of Tatlock with “Oppie:”

It felt very important to understand their relationship and to really see inside it and understand what made it tick without being coy or allusive about it — to try to be intimate, to try and be in there with him and fully understand the relationship that was so important to him.

In the midst of what I recall as the movie’s only sex scene, early in their intimate relationship Tatlock halts sexual activity when a book on Oppenheimer's bookshelf catches her attention. The book is Bhagavad-Gita, the 700-verse Hindu scripture, and Tatlock removes the book from the shelf and then insists that Oppenheimer read from it.

Jean’s described as brilliant medical student, but she’s also adoring daughter to a languages-expert father. Oppenheimer’s having such books, then meeting her challenge to read from original-language texts, would quite clearly be a turn-on, if a momentarily distracting one!

I saw Nolan’s choice of the widely familiar (and widely mis-used) “destroyer of worlds” Sanskrit scripture-quote here in the bedroom, no bomb-related scenes, as a moment of irony and some levity that effectively corrects a mis-perception of both Opperheimer and the meaning of the text. In this scene, Oppie is in a quite literally submissive and humbled position, responding obediently and dutifully sharing text most sacred to him.

To me even more striking is the second scene between them, during their final time together. (Here in the film, the timing compresses two events that in real life were four years apart. First is 1939, soon after Oppenheimer in real life has met Kitty during one of his and Jean’s break-ups. In the movie scene he tells Jean about Kitty’s impending pregnancy, planned quick divorce and their plan to marry before the baby is born. The rest of the movie scene and sequence of surrounding events is Oppenheimer and Tatlock’s last meeting and overnight together in June 1943 — much of which is described in government surveillance of them by J. Edgar Hoover’s sex- and communist-obsessed FBI)

Portrayal of this June 1943 time between them is on my short list of profoundly intimate scenes recalled on film. The two of them are sitting and talking in chairs across the room from one another, and each of them is nude. (To me the impact of this was similar to Nolan’s opting not to show the mushroom-cloud visuals of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings.)

I have come to view the widely quoted “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds” from the Sanskrit otherwise quite inaccurately applied to everything known of Oppenheimer’s character — including the nature of his many faults. And the core meaning of its part in the overall Bhaghad-Gita is vastly misunderstood. It just isn’t a bombastic “I am king of the world” rant of ego-inflation or muscle-flex. So I am glad the movie doesn’t make it one.

Coming across a Rolling Stone piece, THE BIG BANG: We Need to Talk About Those ‘Oppenheimer’ Sex Scenes, late in this writing process, my first response was humorous. The piece reads as though perhaps I saw a different film than this savvy, clever movie critic — who, by-the-way, has some real cred as a journalist, plus adjunct-academic chops at Columbia Journalism School. My mind’s ear hears something like, “Oh my, no, THAT’s not the way to do it, with her distracted by a book from sex to TALK — THAT is not the way people have sex… Oh! It MUST be a problem with the film-making… by poor incompetent newbie sex-scene creator Christopher Nolan.”

Right.

I’m no film critic, but from years of life and sitting with the lives and relationships of a vast and varied range in the therapy room, my sense was, something like this would likely be exactly the-way, for these two.

My response was similar at this writer’s eye-rolling dismissal of the movie’s intrusive visions of Jean-Oppie sex scenes at the 1954 security clearance hearing. This is while Oppenheimer is forced to read aloud intimate details of their love affair — of which we already know from the confrontation-scene that both Kitty and Robert are most fully aware. Again from the shrink in me, I can imagine no couple on the planet in this situation, experiencing what these two have together, who would not both be rocked with intrusive images just about like that in this room.

Actually, I think humor is perhaps my lasting response to this Rolling Stone piece.

🔵

Kitty Oppenheimer

Kitty Oppenheimer biography (from the From Atomic Heritage Foundation Nuclear Museum website ahf.nuclearmuseum.org.)

Katherine Puening was born on August 8, 1910 in Recklinghausen, Germany and moved to America at age 2. Her family had a noble background, and as a child, she would occasionally receive letters addressed to “Her Highness, Katherine.” Kitty entered university a few times in the early 1930s, but dropped out and married her first husband Frank Ramseyer in 1932 when she was 22. The marriage did not last, and was annuled in 1933.

Kitty was married a total of three times before she met Oppenheimer at a garden party in August 1939, when she was 29. The daughter of a wealthy Pittsburgh steel industrialist, her second marriage at 24 had been to young labor-organizer Joe Dallet in 1934. (This, along with her ensuing communist party membership card, must surely have delighted her steel-magnate dad.) The couple had separated briefly, then reunited and moved to France, where Dallet joined communist republican forces fighting in the Spanish Civil War. He was killed in combat in 1937, spurring Kitty to return to the United States and pursue a degree in botany at the Ivy League University of Pennsylvania, which she completed with honors in 1939. At some point after Dallet’s 1937 death, she had quickly married a third husband, a British doctor named Richard Harrison.

In sequence accurately portrayed in the movie, she met Oppenheimer, on the rebound from another split with Jean, in California just after her 1939 graduation and while married to Harrison. Dating Oppenheimer despite her marriage, Kitty became pregnant and Oppenheimer negotiated her quick divorce with Harrison. They married the next day, November 1, 1940, and lived in Pasadena with son Peter before moving to Los Alamos for the Manhattan Project.

As Jean had been, Kitty too was a dues-paying member of the Communist Party USA, which Robert Oppenheimer never was. Neither of the women was Jewish. Kitty’s official communist ties during her marriage to Dallet were a significant factor during Robert’s 1954 security-clearance hearing.

Along with the intense attachment issues apparent in her rapid succession of four marriages before she was 30, Kitty too reportedly suffered from depression. What became her decades-long misuse of alcohol with “sedatives for pancreatitis” likely both exacerbated and masked the depression. Emily Blunt’s film portrayal of the desperately sad Kitty was excellent and moving. Robert’s widely reported known multiple extramarital affairs, often with wives among their social circle in the scientific community, seem unsurprisingly compulsive, similarly sad… None of this in either Oppenheimer the stuff of joy or a thriving psyche.

According to the official website the Oppenheimers did indeed leave their baby son with their friends, the Chevaliers, though they retook custody of Peter before heading to New Mexico for the Manhattan Project.

Kitty’s degree from Penn. was botany, her specialty mycology. (For the can’t make this stuff up file, that’s mushrooms. Seriously, the work with them has resulted in many familiar medical developments, such as statins. ) Though expressing the desire for work in her field, she only did so for a year at the Los Alamos lab. After that she focused on bringing together fellow wives and children for social and recreation activities.

Soon after Jean’s January 1944 death, and Kitty’s intense confrontation with Robert about it portrayed in the movie, Kitty became pregnant again — as often follows such rifts and pivotal points in a marriage like this one. In some cases this can even open, for them all, a life-affirming new chapter if done in deeply intentional, mutual service of the marriage — but also-often not so, when a substitute, compensation, avoidance or distraction from its issues, fragility or durability, and quality.

The Oppenheimers’ second child, daughter Katherine known as “Toni,” was born on December 7, 1944.

Though not depicted in the movie, Kitty left Los Alamos with Peter in April of 1945 and stayed with her parents, citing depression. Again she left her infant child, daughter Toni, in the care of another couple at Los Alamos who had recently lost their own son. Kitty and Peter did return in July of 1945 before the Trinity test.

The devastating lifelong effects of these kinds of attachment-interruptions or abandonments in infancy by parent-figures are thoroughly documented and preventable with clear-headed intervention. Ironically in the Oppenheimer context, the pioneering, enduring work and development in this field of child psychology came largely out of post-war London in working with the many war-orphaned and otherwise traumatized children there.

This was next-generation, ground-breaking Freudian work, some by Freud’s psychoanalyst daughter Anna, and also by those of the London group such as Melanie Klein and Edward Bowlby.

🔵

Later years

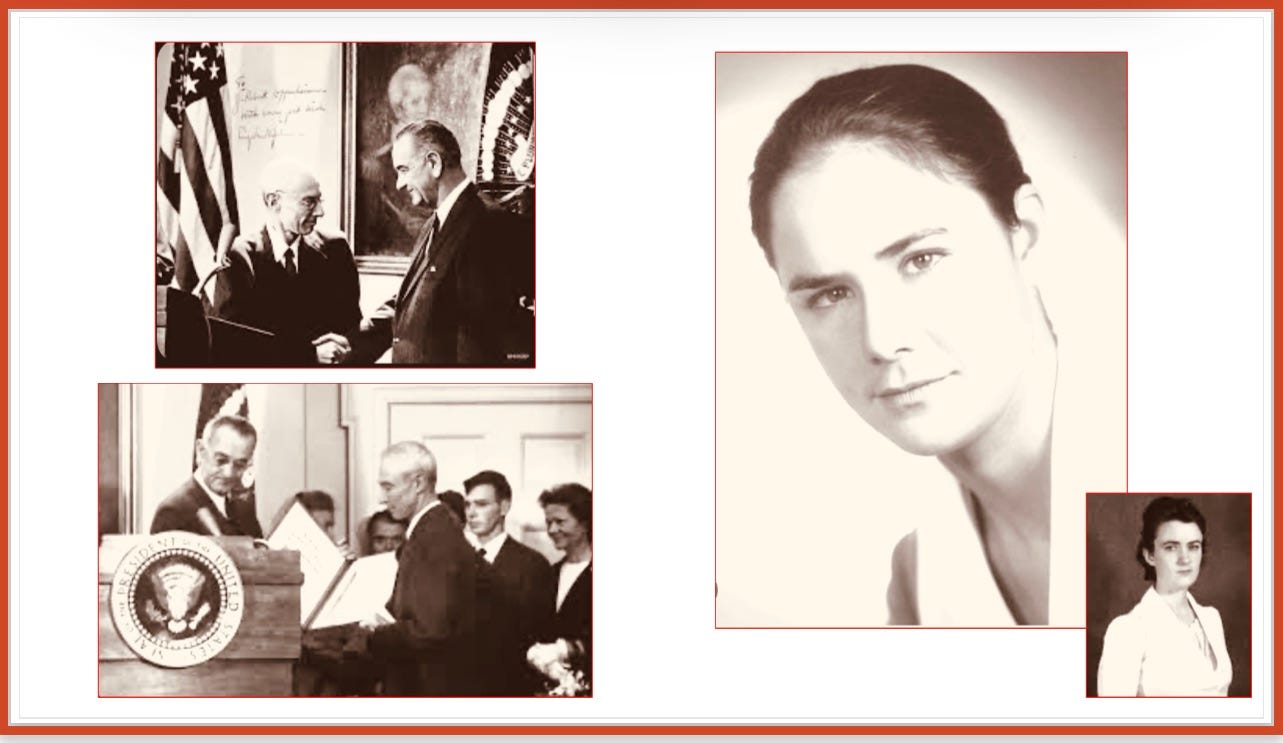

(Pictures at left above) From the official AHF biography:

After the end of World War II, Kitty remained with Robert, moving to New Jersey when he accepted Lewis Strauss’ offer to be director of the Institute for Advanced Study. By this time an acknowledged alcoholic, Kitty somewhat frequently injured herself or was disabled by drinking and pills.

The couple remained together — and Kitty held grudges her husband seemingly could not, as she refused to shake Edward Teller’s hand as depicted in the film.

After retiring in 1966, Oppenheimer died at 63 of throat cancer in February 1967.

Soon after his death, Kitty at 57 began seeing Robert Serber, the recently widowed friend of the Oppenheimers since their days in Pasadena and through the Manhattan Project. (Recall that before the Oppenheimers had met in 1939, Serber had also been Robert’s research assistant. He’d been Oppie’s closest confidant at Berkeley, from the 1936 beginning throughout the Jean Tatlock relationship.)

In 1972, Serber and Kitty bought a yacht and intended to sail to Japan via the Panama Canal, but she became ill during the voyage and died at 62 of an embolism in Panama City on October 27, 1972. Serber and her daughter Toni scattered her ashes, near where they had scattered those of J. Robert Oppenheimer.

Through adulthood Oppenheimer son Peter has remained almost completely removed from public life. Living at the New Mexico family ranch and working as a carpenter, according to offical biographies he is married with three adult children and grandchildren.

Peter’s children and grandchildren have lived somewhat more public lives and have seen and commented favorably about the movie although they did not participate in its creation. Here’s a recap from NBC.

Finally, the Oppenheimers’ daughter Katherine (“Toni”) is pictured at right above.

Caution: The section under this header, between two blue balls, is where we have the third tragedy of suicide, one with particularly affecting elements.

🔵

Katherine “Toni” Oppenheimer

(from the AHF Toni Oppenheimer Biography)

Born in Los Alamos in December 1944 as mentioned, Toni was 3 when the family moved to Princeton with her father’s job as Director of the Institute for Advanced Study. An exemplary student at Miss Fine’s School, she was described as shy and admired for calm temperament. Her noted emotional stability described in the biography made her “the rock of a household that was frequently unstable.”

In 1951 at age 7, Toni contracted polio and the family traveled to St. John in the U.S. Virgin Islands to help her recovery. On recovering from polio she retained a lifelong attachment to the secluded Caribbean island.

One Princeton friend of the family, Robert Strunsky, bluntly characterized the lives of Toni and Peter thus: “To be a child of Robert and Kitty Oppenheimer is to have one of the greatest handicaps in the world.” He attributes this to both parents’ “unique eccentricities.”

By all accounts a healthy relationship with her mother was a struggle for Toni. Serving as the family’s sturdy voice of reason for much of her childhood, she was observed dutifully obeying her mother and picking up cigarettes and drinks for her around the house. By her teens Toni began to rebel. She and her mother were “at each other’s throats all the time,” according to nearby St. John neighbor Sis Frank.

Her relationship with her father was better, at least in some important ways. Oppenheimer had emerged from the stressful Los Alamos environment to become a very loving father, though accounts are mixed on his actual ability to communicate with his children. Some family friends thought Oppenheimer paid too little attention to his daughter, but others saw their relationship as very loving.

What is known is that Robert’s death deeply unseated Toni’s mental health.

She was a 22-year-old, newly minted B.A. graduate of Oberlin Collect when her father died of cancer in 1967. Soon after, in 1969, Toni was denied a position as a translator for the United Nations because the FBI refused to grant her a security clearance. That process dredged up many of the communist charges that had been leveled at her father 15 years before. Toni proved unable to rebound from the two events.

Soon after losing out on the U.N. position, and after two unsuccessful marriages, at age 25 Toni permanently relocated to St. John, becoming a recluse in her family’s old cottage, with few friends on the remote island.

On January 19, 1977, she died of suicide on St. John, a month after her 32nd birthday.

Here the devastating echoes of her father’s beloved Jean Tatlock, 33 years ago also in January, at similar age, and with even a more-than-slight shared physical resemblance in their photos, are… haunting.

Rather than mere happenstance or statistical anomaly, from years in life and therapy room I have come to recognize that this is a common phenomenon between people with profound and emotional (positive or negative) connection. These are deeply unconscious, certainly not intentional or sought, pattern-repeats, re-enactments, attempted rupture-repairs — often over considerable time. These will often take such forms as people finding that they have unknowingly fallen in love, married or left a relationship, experienced a miscarriage, gotten sick, gotten well, experienced a death or had a baby — at the same age, or in other same situations, of important others in our lives.

It’s a reminder-example of how and why routinely noticing and attending to what the unconscious psyche serves-up is life-giving and serves us — rather a way to “keep the proverbial body-and-soul together.”

Conversely, we ignore, deny, beat-down, stuff, or effectively “anti-woke” the soul to sleep at our own peril or misfortune, for the ways we are usually caught unaware and blind are not happy surprises.

🔵

Now the reflecting on so much about Oppenheimer, with all of these interconnected lives so important in his, will need time to settle and steep, with perhaps a few conclusions of relevance and usefulness to come later.

I’ll leave you, meanwhile, with that persistent lingering Hope of the title…

And, that is all I have! Talk to you next week. Much, much more briefly.

🦋💙 tish

•🌀🔵🔷🦋💙

… it is important that awake people be awake,

or a breaking line may discourage them back to sleep;

the signals we give — yes or no, or maybe —

should be clear: the darkness around us is deep.

— William Stafford, “A Ritual to Read to Each Other”